NEW! »Operation Scorpion« available as Kindle edition:

https://www.amazon.com/-/de/dp/B0DNRCCZ3M/ref=sr_1_1

International print publishers being interested in publishing this script are kindly requested to contact the author for the rights:

Book Proposal Factsheet

Author: Wolfgang Welsch

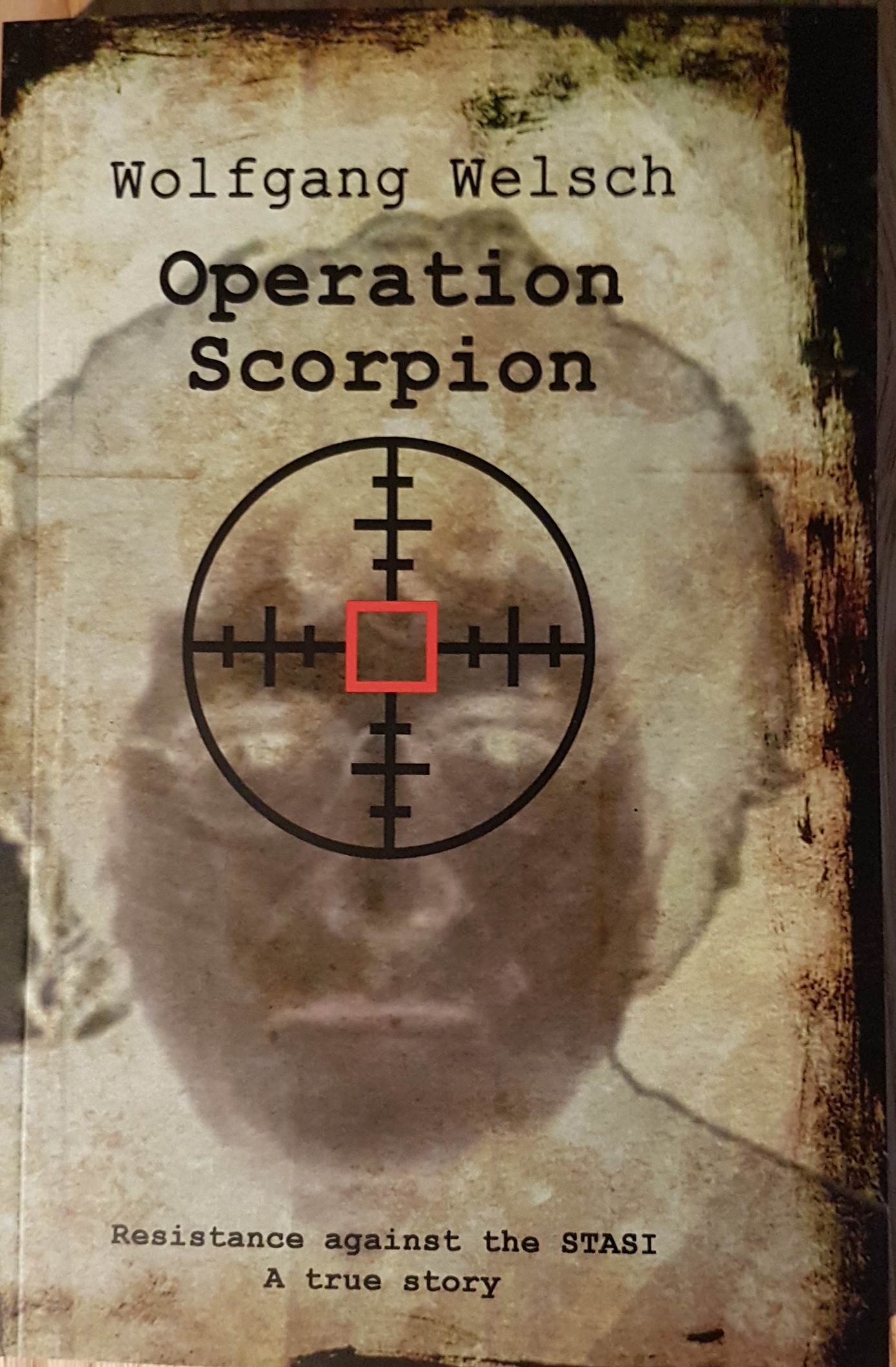

OPERATION SCORPION

My Life as an Escape Agent on the Stasi Hit List

Header

Persecuted by the GDR Dictatorship. The survivor of three assassination attempts. A real life story. Its recurring theme: the fight for freedom.

Biographical Information

Wolfgang Welsch was born in Berlin in 1944. He graduated from high school and studied acting until he was arrested by the East German secret police, the Stasi, and was imprisoned as a political detainee. After his freedom was purchased by West Germany in 1971, he studied sociology and politics, later earning his doctoral degree in England in 1977. All the while, he assisted a large number of people in fleeing from the GDR. In 2015 he was awarded the Robert Schuman Medal of Honor by the European Parliament in Strasbourg for his great and heroic service in bringing about German and European unification.

Story Content

Wolfgang Welsch was just twenty years old when he attempted to flee from East Berlin to the West and was caught and arrested by the Stasi. He was interrogated, mistreated and then convicted of attempted flight from the Republic. What followed was nearly 10 years of incarceration for rabble-rousing and posing a threat to the state. In 1971, his freedom was purchased by the West German government under Chancellor Willy Brandt. Afterwards, Welsch went on to become one of the most ingenious and successful escape agents of his time. More than two hundred East Germans were able to escape from the GDR to the West through his organization. Under the code name Operation Scorpion, the Ministry for State Security then targeted and pursued Welsch as the number one enemy of the state. In a riveting and graphic account, Welsch tells the story of his life and casts an unrelenting spotlight on to one of the darkest chapters in German-German history. In 2004, the story was produced as a made for television movie in Germany.

Unique Selling Feature

This book is the genuine true story of a man who was politically persecuted and tortured by the East German secret police for many years. After being freed from imprisonment, he succeeded in assisting more than 200 people to escape from the totalitarian regime. Consequently, he was the victim of three attempts on his life by the Stasi, which he miraculously survived. He also single-handedly accomplished denouncing the GDR dictatorship before the United Nations.

Target Audience

- General public with interest in suspense-filled and authentic literary nonfiction.

- Readers with a special interest in politics

- Readers interested in East European intelligence and secret services

- Readers interested in the Cold War Era

- High school students at the upper level

- Students of history, political science and social science.

- Teachers who lecture on history, contemporary history, or totalitarian governments

- Universities, colleges, libraries, and national institutions

Bullet Points in Summary

- Narrative Nonfiction / Thriller / Autobiography

- A gripping story and honest portrayal of persecution, torture and targeted killing.

- The unparalleled autobiography of a key-witness to a divided Germany.

- Exposing infamous methods and practices of the Stasi, the East German secret police

- A German bestseller now in its 9th edition of print in 2015

- Television feature film and documentary based on book

- Author owns the foreign copyrights to the book

- An English translation of the book is available

Dr. Wolfgang Welsch

Bestselling Author, Publicist, Expert Speaker and Lecturer

Motivational Statement

As author it is my aim to publish my autobiography and German bestseller in the USA or Great Britain. The working English title is Operation Scorpion. All relevant details to the book are compiled on the enclosed factsheet. Excerpts from the English translation are enclosed as well. My resume and narrative follow below. In terms of copyright ownership, I own the foreign copyrights to my book.

Oktober 2015, Dr. Wolfgang Welsch was awarded the Robert Schuman Medal by the European Parliament in Strasbourg for his great service towards human rights and for his decades of tireless work towards the proper historical appraisal of the SED dictatorship.

Operation Scorpion

My Life as an Escape Agent on the Stasi Hit List

By Wolfgang Welsch

A True Story of Resistance against

the East German Communist Dictatorship

English Translation of the German Original

by Jennifer Sommer Forschner

The Book

Part I

Part I relates Welsch's dramatic resistance to the regime of the GDR in a divided Germany. In 1961, he experiences the building of the Wall in East Berlin. Disgusted by the regime's inhumanity, Welsch feels the resistance growing in him until it becomes his primary purpose. As a young man, he expresses his resistance by reading his poems in public, which often provokes disputes. At East Berlin's Humboldt University, he distributes pamphlets wherein he demands resistance to the communist regime in order to weaken the dictatorship. He writes the script for a documentary film. Finally, he cannot bear living any longer in the "Worker and Peasant" state. He tries to flee, but fails and is arrested at the border. In the cells of the Ministry for State Security (the Stasi"), he is tortured both physically and psychologically. However, this breaks neither his will to resist nor his hatred of the criminal ideology of Marxism-Leninism. He is sentenced to ten years of prison for having committed high treason. Life as a “political” prisoner in the notorious prisons of Bautzen and Brandenburg is almost intolerable. Nevertheless, repeated torture, hunger and solitary confinement actually strengthen his will to active resistance.

During part of his imprisonment, Welsch works on a labor force making large engines for the Soviet Navy. Under extremely difficult conditions, he and a few other political prisoners manage to sabotage the production of these important military exports. Sabotage is punished with the death-sentence, but Welsch is lucky. While a special MfS task force tries in vain to find the saboteurs, talks between East and West Germany begin over the purchase and release of political prisoners. Welsch is one of these prisoners in question. After negotiations with the government, he is taken to the West under cover of darkness by the Secret Police of the GDR.

Part II

After the dramatic crossing of the border in a GDR government bus, Welsch settles down in Giessen and begins to study sociology, philosophy and politics, while simultaneously preparing for his debut as an active underground facilitator for East Germans who wanted to flee. Together with a friend from his days in prison, he fetches a professor out of the GDR. The operation is planned in the Federal Republic of Germany and carried out from Athens, Greece. Welsch flies to Sofia as a courier, delivers a prepared West German passport to the refugee, gives the necessary instructions, and flies back to Athens via Bucharest, Romania. The escape is a successful “David versus Goliath” story: Wolfgang Welsch against one of the best Secret Services in the world.

Welsch is in charge of and takes part in the most daring escape missions throughout the whole of the Eastern Block. Sealed trucks, private cars, caravans, horse transporters and scheduled flights are all part of his arsenal. The route goes from East Berlin via Sofia, Bucharest and Belgrade to Vienna or Frankfurt/Main. Airline flights and diplomatic vehicles are the safest and most effective methods of extracting people from the East. Throughout this part of the book, Welsch relates these stories of liberation in detail. Highlights include a chance meeting with a CIA agent in Athens; the agent seems to know of Welsch's activities and praises him, noting that "they" could not have done it better themselves.

In reply to a hateful article about him in an East Berlin newspaper (“Keine Chance den Menschenschmugglern” - "Don't give the people smugglers a chance" - horizont, 2/80), Welsch sends a telex to the MfS, mentioning not only his chances but also his successes. The Minister of State Security -- the notorious Erich Mielke -- is furious at this provocation and his agency forms a special task force specifically to eliminate Welsch.

Welsch's wife at that time is arrested while attempting to aid an escape in Sofia, Bulgaria. She betrays him, the structure and planning of his organization and all the names known to her. Welsch has no suspicion of this betrayal and frees his wife from the claws of the Bulgarian Secret Service in a spectacular mission. The US Embassy in Sofia participates in this, as well as the Federal Foreign Secretary, Mr. Hans Dietrich Genscher.

During this period, Welsch battles the dictatorship not only by continuously and successfully aiding escapes, but also by publishing condemnatory articles in West German newspapers. With the help of a German political party, he sends a memorandum to the United Nations in New York to urge them against letting the GDR join the community of nations. Of course, the GDR representative at the UN receives a copy of this memorandum. The MfS Secret Police then re-double their efforts to assassinate Welsch.

Part III

For years there is a special “process” in the MfS, in which the various “tactical measures” against Welsch's “criminal human-smuggling gang” are discussed and potential "solutions" to the problem -- meaning, methods of assassination -- are suggested. Around 1978, the leader of the “Central Operative Process Scorpion," MfS Major-General Heinz Fiedler, gives the order to liquidate Welsch. MfS minister Mielke and the Central Committee of the Communist Party (SED) are informed. The murder machinery of the MfS begins to roll into action. An agent is sent to the West. His orders are to assassinate Welsch. This agent, whose cover name is “Alfons”, pretends to be a friend and succeeds in winning Welch's confidence. “Alfons” constructs a car bomb using the explosive Semtex 1A, which he receives from the GDR Secret Service. He installs the bomb under the dashboard in Welsch's car. While Welsch drives on the motorway, the delay-action explosive detonates, completely destroying the car. Miraculously, Welsch survives with only minor injuries.

After this failure, “Alfons” lures Welsch to London. As Welsch drives along an English motorway, a sniper is lying in wait. This time the team of General Markus Wolf, leader of the MfS's Foreign Agent Department, is also involved in supporting the operation. In England, a NATO member state, an East German agent alongside the motorway shoots at Welsch, but misses his target by a hair's breadth. Welsch has no idea what really happened; he thinks that some fool shot at him by chance.

After these two assassination attempts fail to achieve their objective, it is finally time for agent "Alfons" to finish the job. In 1981, he lures Welsch, his then-wife and his daughter to Israel. The MfS has placed a second agent -- a female -- there as well. “Alfons”, who throughout all of this has meanwhile become Welsch's closest friend, recommends a motor home for traveling around Israel. This motor home had been specially exported from Germany to Israel for this purpose. The agents' plan is to poison Welsch using the highly toxic heavy metal Thallium. They consider Welsch's wife and child to be acceptable collateral victims if need be. During a break at the Red Sea, Agent “Alfons” prepares a meal in the motor home's kitchen. He deposits ten times the deadly dose of the scentless and tasteless poison into the food. Though his wife and daughter eat very little of the meal, Welsch alone consumes almost all of the poison. After a four-day incubation period, the first symptoms become visible. Both agents find excuses to leave the Welsch family and return by detours to East Berlin. Mrs. Welsch and the child feel sick for only a short time, but Welsch himself falls into agony. He feels paralyzed, almost unable to move his legs. Finally, the family manages to fly back to Germany, where doctors at the hospital fight for his life. Seriously ill, he remains in the hospital for quite some time. He eventually recovers: another miracle.

As medical experts tell Welsch that such lethal doses of poison cannot be eaten by chance, he immediately suspects the Secret Police of the GDR. After the fall of the Wall, he begins to search his files in the "Gauck department", the agency setup to be the custodian of MfS files. He then begins searching for the assassins, an effort which takes him to England, Greece and as far as Argentina, but to no avail. One day he reads a book on the work of Eastern secret services. The book's description of the methods employed by these Services confirms his suspicion that the attempts to murder him must have been organized by the MfS. Despite meticulously collected evidence and leads, nobody wants to believe him. Both journalists and legal authorities think that his assumption is crazy. Forty years of communist propaganda show their influence on the judgment of the West German intelligentsia. Everyone rejects his assertion that the GDR was in the business of political assassination. He files three criminal complaints, but nothing happens. Only one important news magazine in Hamburg believes him. Three journalists take interest in the case and begin their investigations. Eventually they are joined by a special investigative task force of the Berlin State Attorney's office, constituted specifically to investigate the crimes of the former GDR. Evidence supporting Welsch's suspicions begins to accumulate. In the meantime, Welsch himself has left Germany to live in Costa Rica after receiving further death threats.

The perpetrators of the assaults, and the MfS officials who approved them, are found and arrested. Major-General Fiedler, the head of "Operation Scorpion”, hangs himself in a Berlin prison cell. At a sensational trial, the assassin “Alfons” and his co-conspirators plead guilty. “Alfons” is sentenced to several years of prison. Another of the perpetrators dies of cancer.

Germans today generally do not feel comfortable judging the crimes of the former communist dictatorship; it seems as though most people would rather not know about them. Moreover, it is quite difficult to subject former political crimes and suppression to the justice system of a democracy. There has been no judicial reckoning with the Communist Dictatorship along the lines of the Nuremberg War Crimes that followed the National Socialist Dictatorship.

SNEAK PEAK

PART I: The Escape (p.12)

“Good afternoon.” I held out my ID. “I would like to leave the country.”

A border guard took my ID. “Come with me.” Speaking in a strong Saxon dialect, he ordered me to follow him into the barracks. He opened the door and I entered the room.

“Where is your permit? Where did you enter?”

“I lost my permit in Berlin during all the commotion of the German Festival.

“Where did you enter?”

“I entered at the control point, Wartha.”

The door opened and Charly entered the room with another border guard. “Sooo,” began Charly’s long drawn-out answer. He explained that I had been in Berlin for the German Festival and that I was on my way back to the FRG. This festival was organized by the FDJ, the so-called Free German Youth of the GDR, and was attended, among others, by youth organizations from the West. It was nothing other than a propaganda rally aimed at bolstering the reputation of the regime. My participation should show that I was a friend of the GDR socialist system, which would hopefully make it easier for me to cross the border. Charly played his part very convincingly.

The border guard went to the telephone with my ID. Another guard requested that we follow him. We left the barracks and went to a very large old house. It appeared to have once been a farmhouse, but was now clearly part of the border compound. The border soldier opened a door. “Wait here!” He disappeared with the sound of his heavy boots echoing in his wake.

Inside there was an empty table and several chairs. Ulbricht[1] stared down from a framed photo on the wall and I was beginning to feel nauseous. I went to the window and opened it. I could see the tarred roof of a garage just a few feet below us.

As soon as I saw it, I considered just taking off. Jumping down to the roof wouldn’t be that hard. I still had the key to the car. I’d just throw it in reverse and floor it – make or break!

“What are they doing?” Charly asked, tearing me away from my thoughts. I looked over at him. “They’re probably checking up on my ID or on me, or even on both of us.” A dark foreboding brought us to silence.

I thought of my mother, who lived in Berlin. She had given me my old West German ID shortly before I departed. Of course she knew why I needed it. “Take care of yourself,” she had said as I was leaving, giving me a kiss. As we turned the corner I saw her in the rear-view mirror leaning out the kitchen window.

Had I made the right decision? Of course I had. The only alternative would be to continue living in the GDR. I had no reason to assume that anything in this country would change for the better. The Wall had been standing for nearly three years. Just after it was built on August 13, 1961, I had a first-hand encounter with the brutality of this system of government. On that Sunday, my father, my mother, my brother and I all drove to the sealed off border in Pankow on Wollank Street. We witnessed how travelers that came too near to the line of NPA soldiers and task force members were being clubbed over the head. Everybody was rushing toward the sector border, only to have their worst fears confirmed: crossing was no longer allowed. The border was closed. I could only vaguely remember the national uprising of June 17, 1953. At the tender age of nine years, I had no way of understanding the meaning of all those sacks of flour and the bathtub full of water we kids weren’t allowed to bathe in.

Just three years later, there was something being aired on the “Goebbelsschnauze” [Goebbel’s snout], the “people’s radio”, which had been rescued from the “thousand year empire” and put in the kitchen. I only caught incomprehensible snippets of the conversation. But there was talk of rebellion, freedom and democracy. Then the words shifted to: attack, tanks and death. The Hungarian revolution had come to a bloody end. No matter where or what, the aim was invariably to keep socialism alive. And this was always done by force and against the will of countless people.

Later, in school, I once stuck a pin into a poster, right into the head of Wladimir Iljitsch. I was shocked by the reaction. The principal came and had a long talk with us. He was visibly worked-up. I will never forget the furious look on his face. The class teacher stood by silent and somber. In those days the sentence “socialism will triumph” appearing at least once in any given essay was a guaranteed “A” in German class.

The cold war was raging. It seemed all positions had been delineated and were uncompromising. The first deaths at the “Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart”, as those in charge of the newly erected wall liked to call it, left no uncertainty as to the magnitude of their determination and inhumane ways. The GDR had been transformed into a massive concentration camp. The people most directly affected were those living in the divided city of Berlin. They were in a state of paralysis and so was any urge to flee. The number of attempted escapes was close to none.

Gradually, people began reestablishing themselves and coming to terms with the new situation. Only a brave few dared to attempt escape. This was seen and heard about on West German television. Tunnels were dug from West Berlin and specially equipped trucks, trains and ships broke through the border that was growing increasingly harder to cross every day. Many just gave up. I heard many asking, “What other option do we have? Here we are and we can’t do a thing to change it.” I couldn’t and didn’t want to resign myself to that.

I wanted to be free. I wanted guaranteed rights and personal freedoms that should be afforded to every individual. I loathed anything that took place on a large scale, be it big happenings, mass rallies, or mass-participation sports.

What did I have to lose? Well, I could lose my contract with the GDR-Television network, or the first offers for roles with the DEFA [the state film monopoly in the German Democratic Republic] I had received while still in training at the East Berlin drama academy. I could miss being able to participate in the huge poetry evenings in the auditorium at Humboldt University. When Sarah Kirsch had read her poetry there, unaffected by any of the party directives, she was a breath of fresh air and the notions freedom and of free speech swept through the auditorium. On the other side, there was the polarizing poet Wolf Biermann, who read tentatively about his ‘number seven bus/that needed to be washed’. Hermann Kant, president of the GDR writers association, preached on the class-struggle. And all were giving high acclaim to the party in their own special way. Each of them was a member of the SED party. Then there were those abominable Stalinist singers, the “Oktoberklub”, performing their sophomoric tribute to the GDR prison guards.

All the while, outside in the lobby, a swarm of people had gathered who were outraged by what was going on inside. They were standing around with hopes of hearing some poetry readings. Momentarily, I grabbed a chair, stood up on it and began reading my own rebellious poems. Several there, who were loyal to the party, found this a provocation. It wasn’t long before I was forced to get down from the chair.

It was on that night that I decided to leave. My decision was final and irrevocable. The strength and the will to do so grew inside me like an unstoppable force. My escape plans would take another several months to materialize. And now, the day was at hand.

Inquisition (p. 22)

A few days later, I was fetched again: “Right Side, come with me.”

A Stasi lieutenant in uniform sat behind a desk in an office that I had been led into. Next to him lay an ancient typewriter. He was paging through a file.

“Have a seat.” He pointed to the chair.

He appeared to be around forty with a broad face that had a crude expression on it. His fingertips were discolored with a brownish tint. He was obviously a heavy smoker.

Without any further preface, he got right to business: “In the next few weeks we will be questioning you on all aspects of your life, about your recent act and what led up to you committing this act. We have plenty of time. I am sure you have noticed that already. It is completely up to you, whether you cooperate with us or not. Accordingly, the report and protocol will reflect your willingness. I have read the assessment of you submitted by the prison. From that report, I have concluded that you are recalcitrant and refuse to submit to our authority.”

“Then you have been misinformed. Please list my concrete offences.” My ‘telephone conversations’ using Morse code and my occasional window contact had all gone unnoticed up to that point.

His head jerked forward and his eyes grew large. “You are in no position here to be making demands. What gave you the idea that you should be allowed visitors during the investigation?”

“That is based on my knowledge of due process as it is afforded to citizens in the Federal Republic.”

“But we aren’t in the Federal Republic, we are in the GDR. Only our laws have any validity here. We have enough time”—he paused for effect— “to review your misconduct.”

“I am glad you are bringing up the topic of misconduct,” I replied facetiously. “In particular, the magistrate recently explained to me that my attempted escape is considered a crime. So what’s the real case here?”

“I’m not here to argue with you, but to establish the facts. You will now answer my questions. And I advise you to be truthful.”

What followed was an endless game of “question and answer”, whereby the more he asked, the less I answered. He recorded everything on paper. Around lunch time I was picked by a guard called a “porter” to go eat.

Afterwards, the proceedings continued. When the interrogator had finished, he typed up everything on his typewriter and pushed the finished protocol across the table to me to sign.

“If something isn’t true you can correct it.” He handed me a pencil.

I read over each page.

Even the first paragraphs were distortions of what I had actually said. He had twisted my words around to fit his viewpoint. I made him aware of that fact.

“Fine, then make your corrections.” I did just that. He watched me indignantly, but I didn’t let that distract me. After I had read through everything and had crossed out and corrected what I could, I went to sign it with the same pencil.

“Hold on!” he interrupted me. “Sign with this.” He handed me an ink pen.

A few days later it dawned on me what he had been up to, or rather what nasty little trick he had employed. All of my pencil corrections would be erased, thereby falsifying the protocol. Only my signature in ink would remain as genuine. Later on, argue as I might, my signature was legally binding. Later, the interrogation officer would betray himself through his own stupidity and lack of self-control and this is how it came about:

At some point, he confronted me with a previous statement I had allegedly made. I disputed having made the statement. Furious, he grabbed a binder out of the safe and after flipping through it, he ripped a protocol out of it and held it up.

“And what is this? Do you deny that this is your signature?”

“May I see that?”

“For what? This here is your signature, is it not?” He tapped his finger on my signature. I stood up from my stool and walked towards the desk.

“Back to your seat or else I’ll call for the guards,” he shouted. But it was too late. I had already spotted the deception. A short glance at the page was enough to tell that not a single one of my corrections remained.

I sat down on my chair again and explained: “You manipulated the interrogation protocol. All of my corrections have been erased. How appalling is that?”

The interrogator lit up another cigarette, stood up and came at me.

“Do you realize what you just said?” he asked as if ready to pounce but stopped right in front of me. He had a wide grin on his face. I felt steadfast and strong because I possessed the truth.

“Yes, let me repeat myself. The protocol has been manipulated and from now on, I will not sign another single document of yours. So, you can write whatever you want from now on.”

He strolled over to the window and back again. “How dare you accuse me of falsifying documents! You are insulting and slandering the investigating authorities. Don’t you understand where you are and what you are?”

“How could I possibly forget that, even less so n...” Mid-sentence my world exploded and stars began dancing around my head. I was struck with a hefty punch to the middle of my face. My head cracked against the corner of the wall and split open. I had the sweet taste of blood in my mouth. I was stupefied and the room looked fuzzy. I saw the interrogator as if through a fog. He was standing over me once again. I put my arms up to block my head in self-defense but I was completely at his mercy. An acute surge of anger took possession of me. I felt it coursing through my veins. My left eye swelled shut. I slowly uttered the words: “You forged the protocol. You are a forger!”

Another wallop tossed me from my chair. It was forceful and with precise aim. My head knocked hard against the wall again. I presumed my nose to be broken. Then I didn’t feel anything at all.

When I came back to consciousness, I was lying on the floor. I felt sick to my stomach and began throwing up non-stop. The gagging was relentless. I continued just lying there on the floor.

I heard the interrogator talking on the phone.

It didn’t take long before the door was thrown open and in walked two figures. They walked cautiously around me, trying hard not to step in my vomit.

“He attacked me,” I heard my interrogator saying.

“Get up you dirt bag!” Somebody kicked me in the side with his boot.

“Stand up,” screamed the interrogator. I continued lying on the floor.

“What’s wrong with him?”

“He’s faking it.”

“Yeah maybe, but he’s also bleeding. I’ll notify the attendants.” The door closed. I passed out again.

When I came back to my senses I was lying on my back. A man in a white coat was bending over me. Suddenly I was being pulled by my arms and I was hauled out of the room. Occasionally my strength would give out and my legs would drag behind me. I was brought back to my cell and was thrown down on my bed. The door closed and the bars clanged behind it. I was all alone with my pounding head.

“You cowardly and cunning snake,” I heard myself muttering. Somehow, I had a strange sense of satisfaction despite all the pain I was in. I had exposed the man. I had seen through all of the threats and blackmail, forgery, lies, malt coffee and cigarettes offered; all under the guise of an interrogation. Their inquisition wouldn’t break me. I was determined not to let it come to that.

I pushed the alarm button and the “chuck hole” flew open.

“What do you want?”

“Please go get a doctor. I am injured and in pain.” The flap slapped closed again. Shortly thereafter, I heard keys jangling. The door was opened, but instead of a doctor, it was someone I didn’t know. An overly fat civilian with droopy cheeks entered the cell. The guards remained outside.

“So, what do you want?”

“Are you a doctor?”

“I am the director of this institution.”

“That’ll do too. Please take a close look at me. Feel free to get up close and have a good look at me. I most likely have a serious concussion. And could you please turn on the water so that I can wash my face and head wounds? What I really need is a doctor.”

“You only have yourself to blame for that, Right Side. You attacked your interrogator.”

“Oh and how would you know that? Were you present? Why would I do something like that?”

“Well, you are in here for a reason.”

“I’m not in here because I’m violent. I was beaten up by the interrogator because I confronted him on forging documents. This”—and I pointed at my head— “was his reaction to that.” I explained to him in great detail what had gone on during the interrogation.

His turned down pig snout grew even narrower as he snorted. “Right Side,” he wheezed through his teeth, “If you don’t shut your damn mouth and quit your lying right now, you just might slip and fall again. Then your other eye will swell shut too. I’ll permit you to lie on your bed for the rest of the day. There will be no doctor. I’ll turn on your water now so you can wash your face.” He turned around and squeezed himself back out the cell door. It closed and the water was turned on.

I gently washed my face and head wounds. The director of the institution, better known as “pig face”, had lived up to his name. That wouldn’t be my last encounter with him.

I was left feeling so very alone and so very lonely.

The Execution (p. 79.)

It was already February. The heating was only turned on for a short time each day. I spent the rest of the day walking around wrapped up in my blanket. One evening my cell door was opened imperceptibly. Outside there stood countless uniformed Stasi men along with two or three civilians. No one said a word. One officer with three gold stars on his epaulettes stepped into the doorway. I noted that he was a first lieutenant with astonishing calmness, as if I were a mere observer to a set of events that didn’t concern me.

“Step out,” he said, eerily hushed.

No sooner was I out of the cell then I was latched onto and restrained with both of my arms bent back behind me. I felt my hands being fastened to my back with handcuffs. Someone whispered in my ear. “One sound out of you and you are a dead man.”

I was gripped with fear, which spread through my body and slowly began to petrify me.

I was taken to a room. Someone opened the door. A cluster of people stood around me. No one spoke a word. They appeared to be waiting for something. The door at my back opened. In the reflection of the darkened window, I saw uniformed men entering the now crowded room with machine guns slung around them. Before I could even contemplate being intimidated, my head was held in place from behind while someone bound my eyes with a cloth and tied it into a knot, giving it a sturdy tug at the back of my head.

I was turned about-face 180 degrees and pushed forwards through the door and then out of the room and down the hall, taking unfamiliar twists and turns. I could see nothing but pitch darkness before me and I lost all sense of orientation. Most especially, it was the hush-hush of the whole procedure that multiplied my dread.

Suddenly, I was struck by the cold night air. We were in the courtyard. I knew it from the recess cells. We zigzagged down a path I didn’t think I had ever been down before. A few restrained commands were given and we remained standing—somewhere in the courtyard.

I was pushed backwards up against a wall. In that moment a diesel generator came on. I knew that sound. It was always turned on when someone was being beaten to drown out the sound of the screams.

A voice sounded directly in front of me, which, despite the generator, was clearly audible. The voice stated my name and my birthdate. I was stricken by a crippling terror. Nobody beat me, nobody flogged me. Something utterly unfathomable was taking place here. In a flash, the details pieced themselves together in my mind: Weapons, blindfold, hands bound behind my back, night, wall, diesel… Oh my God, they don’t intend to kill me, they aren’t going to murder me right here and now on the spot?! My hair stood on end and a shudder ran through me. Everything inside me froze. I was seized by mortal fear.

“…is hereby, by virtue of a special court order in absentia, sentenced to death for grievous crimes against the state of the German Democratic Republic. The sentence is to be carried out immediately.”

My mind was vacant, incapable of reflecting or reacting, and incapable of crying out.

“Firing squad, attention!” I heard the order given. There was the stomping of boots. “Release!” I heard the rhythmic clapping of metal, the clanking of gun locks.

The generator was humming.

My knees began knocking. In mortal agony, a single thought clawed its way into my brain: No one will ever learn of this. My death will go unavenged. I underestimated them…had done too little. Murderers! “Murderers!” I wanted to scream out, but I couldn’t make a sound.

“Aim!”

Why me? Why all this hatred? What did I do to deserve it? My entire body was quaking. I felt my heartbeat pounding in my throat. Dear God…

“Fire!”

………………

………………

The generator was humming.

Is there diesel in heaven?

Am I dead?

I was living and breathing.

The penetrating odor of the diesel stung the insides of my nose.

I tried to wiggle a finger. It responded.

I was truly alive and was still standing up against the wall. I listened motionlessly for a new command. There wasn’t a sound. There was only darkness and the noise of the diesel generator.

All of a sudden I was grabbed by the arms. As if in a trance, I allowed everything to happen to me. Silently we traversed corridors…the scent of the prison...warmth…a cell…My blindfold was removed. The handcuffs were too. From the front, I was slipped into a white jacket and its extra-long arms were tied around to my back. Everything happened wordlessly. It was a nightmare scenario.

A shove came and I fell onto a bare wooden pallet. The door shut and the light went out.

Slowly, ever so slowly, the fear started to ease up. I could feel my pulse again and sensation returned to my body. I couldn’t muster a thought though; I just lay there mutely, rolled up in a ball on the pallet.

Then I began to cry. Voicelessly, as if I were afraid someone would hear me. All of a sudden I felt guilty, terribly guilty, and so I began to cry even harder. And there I lay, between dozing off and sobbing away, as I disintegrated into a state that seemed like nothingness.

The Student and the escape agent (p 107-108)

By May, I was approached by a friend in West Berlin who asked me if I knew how to get people out of the GDR. He knew a family in East Berlin who had come to him with the request some time ago. Up to then, he hadn’t been able to help them. I was interested and he offered to travel with me to Berlin-Zehlendorf to where relatives of this family were living.

They received me warmly and came straight to the point. The man told me about his brother, a surgeon at the charity hospital in East Berlin, who had made continuous efforts to leave the GDR. He hadn’t turned to the services of a well-known West Berlin escape agent because of his unreliability.

“How big is the family?”

“There is my brother, his wife and two kids, a girl and a boy, four and six years old.”

“I would have a way for helping your brother get to the West, along with his family, this summer—risk-free.” The man got up and started walking around the room. His wife poured me another cup of coffee.

“How do I know that what you say is true?” Do you have any idea what you are talking about? They have two kids.” He paced back and forth in thought.

“I know the consequences; I therefore repeat my offer. I can’t guarantee anything. You will have to trust me. I aided in an escape operation this very year. I can’t tell you details for safety reasons, but I can tell you I take a personal interest in having your family leave the GDR unscathed”.

I then gave a brief synopsis of my story so he could better understand my motives.

“There is something else you must know. The escape plan is not cheap. Careful planning and preparation demand a price. You will have to put up about 20,000 marks. After successful conclusion of the operation, I provide you with a tally of all the costs that were involved. Facilitating escapes is not a business enterprise for me.

The man talked with his wife. They readily agreed.

“We appreciate and accept your offer. My wife and I hope that all will go smoothly.”

They then gave me all the necessary documents, including photos and an exact description of the family’s residence. We then discussed the terms of payment. The amount would need to appear in my account by the following week at the latest.

We said goodbye. My friend was left speechless. Lives and the future of a family were now in my hands.

Just as soon as I was on my flight back to Berlin and began putting together the details of the escape plan, one big problem occurred to me: the passports. Where could I obtain passports, containing the names of those concerned? Where did Dieter get the passport he had? It was clear I needed to go to him.

In his student dorm room, I explained the situation to him.

“There is one possibility. The people involved are as sensitive about things as we are. They want to be sure that nothing amiss will be done with the passports, if you know what I mean. The passports need to be returned as soon as the case is closed and the people are safely here.”

I breathed a sigh of relief. “Of course. The passports will be returned.”

I learned that the passport identifications came from government institutions that were secretly aiding GDR citizens who wanted to flee. The next thing I needed to do was to contact the family in East Berlin. For security reasons, contact by telephone or letter were not viable options. Due to my entry ban, I would not be able to go to the “Worker’s and Farmer’s Paradise” myself. Under the circumstances, I had no other choice but to send a courier, someone trustworthy and able to inspire confidence.

A particular fellow student of mine came to mind who I deemed suitable for the job. Of course, as soon as I asked him if he would be willing pay a visit to someone in East Berlin, he understandably asked me why. I let him in on the crucial details of the plan and the role I was asking him to play.

He didn’t seem taken aback; instead, he was curious. In a snap decision he agreed. Naturally, I would take care of the expenditures and daily expenses of his trip.

Afterwards, I called the brother in West Berlin to get more information from him. I also needed to have two recent passport pictures from each of the adults; the children would be added to the mother’s passport, so I didn’t need pictures of them.

The date of the operation was set for July of that year. The kids had summer vacation, and it would be inconspicuous for the doctor to take a vacation during that time. That left me with only two months to get everything ready. That would have to be enough time.

In my search of a discreet producer of rubber stamps I stumbled across a small business in Giessen that specialized in such unusual jobs. I engaged the owner in a little conversation, which I purposely steered in the direction of the East-West problem. I was fortunate. The man had relatives in the GDR. The circumstances were relatively unknown to him. But he was totally against the political situation in the GDR. That was how I, by necessity, came to trust him. I laid my passport on the table and pointed to the Bulgarian entry and exit stamps therein.

“I need a template for each of these. The space in the middle where the date appears has to remain free so that a date can later be added.”

He asked me if the stamp would be employed in the Federal Republic. I told him no and added, “You can be certain that nothing will happen to cause you any trouble. This has to with an operation which helps GDR citizens escape.”

He was satisfied with that and nodded, while announcing that he would produce the stamps.

“Hopefully it will all go well.”

“You can count on it. What I need, though, is a perfect reproduction. The minutest of details has to match the originals.” The master stamp maker laughed.

“I think I can manage that. You’ll see. When I am finished you won’t be able to tell the difference between my rubber stamps and the originals.” After we agreed on a price, I left the store.

At a Giessen travel agency, I gathered all the information regarding the flight routes from Sofia to Bucharest to Belgrade and to Vienna and to West Berlin via Frankfurt/Main. I had checked routes with summer flight airlines “Balkan Air”, the Romanian airline “Tarom” and German “Lufthansa”. In Bucharest, the escapees were to stay for a short spell—what I liked to call a “low-profile buffer”—of three to four days, so that their travels there would look like a tourist vacation. After that they would continue on to Vienna, and from there they would board the next plane to West Berlin via Frankfurt/Main.

I would purchase the tickets for the flight from Sofia to Bucharest in Giessen. GDR citizens were allowed to fly with tickets bought in the West. It was important to book the connecting flight from Bucharest to Belgrade and pay for it in advance, as well. Booking and paying for tickets directly at the airport there was problematic under the chaotic conditions at Romania’s main airport. It was especially difficult for GDR citizens, who didn’t have any sense of confidence whatsoever while abroad. That is how they were treated by the Bulgarians, their ideological “brothers”. The “poor Germans” with their meager contingent of non-exchangeable GDR marks, which tongue-in-cheek were called the “Papp-Mark” [cardboard marks]. What was more, the few travel agencies in the Eastern Bloc were brimming with spies from various state security services, at least in my estimation.

Part II: The Memorandum (p 114 – 117)

At the conclusion of the winter semester I had managed to complete and receive grades in all my classes. I had now attended one full year at the Justus Liebig University. My studies demanded a lot of me, but were increasingly satisfying to me. At the university library I read all the books on German history I could get my hands on, as well as many works on German secret services. They were indispensable to my dissertation. However, the information available on the Federal Intelligence Service was as sparse as what was available on the Ministry for State Security. Despite a letter of recommendation by my professor, I hit a wall of silence in my requests at the Intelligences Services.

In no way did my studies cause me to neglect my intentions of openly decrying the ongoing crimes of the SED State. An opportunity arose when I made the acquaintance of Gerhard Loewenthal, the moderator of the TV program ZDF-Magazin, which was very heavily criticized in the West and very popular in the East.

The co-moderator of the show, Fritz Schenk, had me on the show that aired May 9th for a discussion over the prison conditions in the GDR. This was the first time a person directly affected could openly name the crimes of the regime on television.

The ZDF show was followed by a radio show on a station in Cologne called Deutschlandfunk. In a feature to which I was invited by Karl-Wilhelm Fricke, the leading expert on the MfS and an author, I was able to reiterate that it was essential and possible to oppose the SED Dictatorship’s resistance.

The Swiss newspaper Der Bund supported my cause with a full page article concerning the crimes of the SED State. The British Evening Post wrote an article in the same vein, and even India’s Standard did the same. More media followed. I didn’t like it at all, however, when the Passauer Neue Presse announced that a student of the University of Giessen wanted to write his doctoral thesis on the GDR’s Ministry for State Security.

With that, the initiation of retaliation against me was only a matter of time. Just the same, I still felt rather secure with the border to the GDR lying hundreds of miles away.

In early summer, news was consolidating that the GDR had put in a request for inclusion in the United Nations. The date announced for the vote would be at the UNO general assembly to be held on September 19 of that same year. There wasn’t a single cry of outrage to be heard from anywhere across the political landscape of the Federal Republic. Quite to the contrary, in the opinion pages of newspapers such as Die Zeit and other commentaries, the talk was that the GDR was entitled to membership and that the FRG should finally acknowledge the state. That was certainly an attack on the claim to sole representation for Germany by the FRG and would require giving up its legal positioning in constitutional law.

What could be done to stand up against the audacious demands of the SED Dictatorship? One would have to take the protest all the way to the place where the GDR had directed its wish for recognition as a humanitarian state—to the UNO in New York. The United Nations just had to be told the truth about the lawless regime in East Berlin, beyond the diplomatic considerations and convoluted concepts of appeasement.

So I began my work on a “memorandum” in which I listed the human rights abuses and crimes of the SED Dictatorship and warned against permitting the GDR to join the UN. I wasn’t clear at that point on how my memorandum would actually reach the person it was addressed to, or whether its contents would be taken seriously, or how it could be brought to the attention of as many member states as possible, or better yet all of them. At the end of the day, the United Nations was an organization of many countries. I on the other hand was just one person.

At the beginning of August, I was finished writing. I had put together eight pages of reasons which urgently spoke against the inclusion of the GDR into the community of the United Nations.

After listing all of the institutionalized crimes of the GDR regime, I referred to the countless prisons, camps and psychiatric hospitals containing political prisoners at that very hour. What was more, the GDR referred to the United Nations as a “criminal organization,” one into which it now sought inclusion.

They had put it like this in a written indictment against me: “…by Welsch turning to the UNO in an inflammatory and defamatory letter, he thereby made contact with a criminal organization, which is a punishable crime according to…”

As to the vote on the Federal Republic’s application, a delegation would be put together in equal numbers from every party represented in the Bundestag, and would travel to the seat of the UNO in New York. I saw an opportunity therein for getting my letter to its destination.

So at the beginning of August I canvassed every party central in Bonn. The SPD “Baracks”, as the Ollenhauer House was named, gave me the cold shoulder. The FDP didn’t want to get involved at all. The CDU showed some interest, but didn’t want to stick out its neck too far. I was therefore greatly surprised when a CSU member led me to the office of CSU representative Franz-Josef Strauß. I was met there by his office manager, Voss.

I presented him with my cause and handed him over the memorandum. He seemed highly interested and held out the prospect of an appointment with representative Strauß, Franz-Josef Strauß.

Mr. Voss kept his word. A few days later I was openly received by Franz-Josef Strauß. After an unusually long briefing, in which he questioned me on my imprisonment in the GDR and on what the grounds were and how I was treated, as well as on my present undertakings and my political orientation, he finally took the memorandum in hand. He focused and read it quickly through to the last page. His short analysis made it obvious that he had understood everything precisely. He endorsed my description of the GDR without compromise. He read individual passages again out loud and determined that they corresponded with his convictions.

He thanked me for my “patriotic involvement”, as he put it, and promised to campaign for the memorandum to be taken by a CSU member of the delegation to New York and handed over to the secretary general of the UNO.

“What will become of it then is not in our hands. But you can be sure that it will certainly get lots of attention. The problem is generally known. The meaningful thing about your paper is that someone directly affected and with a knowledgeable voice points a finger right at this German sore. Do you know that you are doing a great service to Germany by that?”

I didn’t know that. I just wanted to bring to light the endless stream of lies, heresy, deception and violence that was thickly and brazenly spilling out of East Berlin, and would soon reach all the way to the shores of New York.

He wished me much success on my path and added at the end, “I understand you are studying in Giessen. That’s in Hessen. Why don’t you move to Bavaria? We, the CSU, could use such young involved people. You are always welcome, if you know what I mean by that.”

I understood very well. But at that moment I was floating on a high from my achievement.

The “Bulgarian Connection” (P. 135-136)

Requests for escape aid for the year 1976 were already coming in. As before, the main focus was on the Balkan route. The only difference was that I would spend the majority of my semester break in Greece. I had decided to put the tip about Platania to the test. That way I could combine business with pleasure. By that time, I left courier services and trial flights to others, because my dealings had grown greatly in number and each new mission brought increasingly incalculable risks with it.

My wife had carried out a first trial flight that year with success. There was no reason that she couldn’t play courier as well. Moreover it would cut costs. Two years after we had been wedded she had become familiar with the essential preparation procedures for the Balkan route. She knew that these trips were not dangerous. In total I had planned six escape enterprises for that summer. I had taken all the passports, tickets and other documents with me to Greece. I had an answering machine, which meant I could retrieve messages from anywhere via a code. That kept me in touch with my clients. From Platania, I was able to take care of the last bookings. As soon as I had the flight confirmations, I was able to enter the requisite date stamp. At that time, red with green stamps were in use with a so-called seamless color transition.

On Wednesday, the 18th of August 1976, my wife flew from Athens/Hellenikon to Sofia with a beauty case which contained the documents sewn to the inside. This time we were helping a GDR couple from Hartung /Lürmann to get out. As I was driving her to the airport, my wife suddenly proclaimed that she had a bad feeling about the trip. As a precautionary measure in order to keep up the guise, our two-year old daughter Nathalie flew with her. Where did her dark premonition come from? I thought of the waiting refugees who had put all their hope in us.

“It is your decision, your mission, your flight. I see nothing which should stand in your way,” I said to her. So she took the flight.

But her feeling hadn’t betrayed her. Had she told me beforehand exactly what had happened on her trial run, I would have had more to go on than her vague premonition. In fact, I would have been pretty sure that the cover to our operation had been blown. Instead, I had stayed behind, clueless, and with the self-assurance that I had done everything humanly possible to get the couple out of Sofia.

My wife knew full well the foremost principle in escape assistance, which is absolute secrecy. No outsiders whatsoever—and clients and their family members were to be counted as such—were to be let in on any details. What I later learned (not from her) was that she had breached this basic principle in an outlandishly imprudent manner.

She had met a black student from Ghana in Sofia. It was clearly her own free choice to take up with this man—nothing forced her into it. She failed to uphold her sworn oath of nondisclosure by giving this man, after exchanging only a few words with him, her real name, as well as her address in the Federal Republic. To add to that, she gave him a photograph and promised to return to Sofia again soon. She had behaved like a love-sick teenager, not a courier.

Then began an exchange of letters between the two of them behind my back. The icing on the cake was the picture-postcard that she had secretly written and sent to the man from Ghana, in which she had written details that in the end busted our secret mission: “Arrival from Sofia 8/18/1997, 11:30 pm with Tarom. Pick me up please, Hilde.”

That is just what the “the student from Ghana” who called himself “Mangali” did. Apparently he was a decoy working for the Bulgarian State Security in cooperation with the MfS, who had caught on to the disappearance of so many GDR citizens in Bulgaria.

The fact is that from the moment she arrived in Sofia she was under heavy surveillance. A task force of MfS investigators, who had been alerted by their Bulgarian comrades, had arrived in Sofia. The MfS Major General Fiedler did not want to miss the occasion.

Death in Sinai (p 172-174)

The sight-seeing tour of Jerusalem that we had decided on turned out to be pretty strenuous. It was hot. Peter and Susan accompanied us to the Wailing Wall, the Temple Mount, the Knesset and to visit the Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum. Despite our being on vacation, and my daughter drawing lots of attention, Susan spoke hardly a word with us. Perhaps she felt concerned that her English might be found wanting in light of my fairly good English skills. She was just as uncommunicative while eating a falafel sandwich as she was while viewing the Wailing Wall or the golden copula of the Dome of the Rock.

The night we spent at the King David helped us to forget all grievances. Even the horrendous bill at checkout didn’t change that. But as we were back in the camper and on our way, the atmosphere didn’t improve. Thankfully, Susan had disappeared out of sight during the drive, but at our very first stop, my wife reported to me that she hadn’t spoken a word and just played with the kid. Well at least there was that.

We drove on through the West Bank. The road went on for miles on end along the Dead Sea coast all the way to the oasis of En Gedi. We took a break there. The bubbling springs, the very same as described in the Bible, provided a lot of refreshment from the heat of the Negev. From there it was just a short walk to the Dead Sea. In the briny water we laid on our backs to try out for ourselves what we saw others doing. The salt content of the water is so high, that you could, as Peter demonstrated, lie on your back and read a book.

Soon we drove on to Eilat, located at the northern tip of the Red Sea. Here too we treated ourselves to a short stop. Our actual destination was the southern tip of Sinai, Sharm el Sheikh. The Sinai had been claimed by Israel in 1967 during the Six Day War and was still in its possession. So, without any problem, we were able to pass by Taba and enter the desert. Other than a few Arabs, Bedouins with their camels and tents, and a few Israeli tourist stations, there was nothing other than a sandscape to be seen, the contours of which shimmered in the hot air and melded into the horizon. After only a short stop it quickly became clear to us that there is nothing but dead stillness in the desert. That same evening we reached Sharm el Sheikh. There at the far end of the Sinai, it was boiling hot—over 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the sun! The air glimmered. It was impossible to walk barefoot on the beach.

We rented an air-conditioned bungalow and spent the night there. None of us felt hungry at all, but we couldn’t seem to get enough to drink. A bath the next morning did nothing to help cool off. The water was as warm as the goat milk in a Bedouin’s pan. Even the few leaves left on the palm trees were hanging limply. In a word, the heat was murderous. That is probably what was on his mind when Peter began pushing us to leave earlier than planned.

“Let’s go north and visit Lake Tiberius or the Golan. It is cooler there.” he concluded.

It was truly no fun at the Red Sea. So we took off and drove back in the direction of Eilat. It was late afternoon when we stopped just south of Eilat. In the sea, about 300 feet out from the beach on a small rocky island, the ruins of a Byzantine fort jutted out. The Israelis called this Coral Island. A few small bungalows with steep pointed roofs were crowded onto a long beach. Next door, there was a large restaurant which was closed for lack of customers. Our RV was the only one to be seen. For the first time in a long while, I started to feel hungry. The temperature had dropped to a tolerable 85 degrees.

“You guys can go swimming. I will make dinner.” With this Peter sent us to cool off in the sea.

“I am going to make hamburger patties and salad,” he announced to us on the beach as he was already on his way.

About 40 minutes later, we had already swum to the island and back again and had visited the ruins and were lying in pools of water on the beach, when he called and waved us over. We walked back. In front of the bungalows there were wooden tables with benches set up. Just behind us was the parked Bedford. Haack had set the table and the food was spread out on it. A large bowl stacked with hamburger patties and another bowl of mixed salad adorned the table.

I didn’t have to be asked twice before I dug in. The hamburgers were delicious, perhaps only because after days of fasting due the heat, I had developed a ferocious appetite. Nathalie too dug in, but quickly had run back down to the beach to play. My wife, who is not crazy about meat, ate some of it anyhow. Out under the open skies and with good company, everything tasted especially good. With every bite I took, I took in another dose of thallium. One of its characteristics is that it is tasteless and scentless and can therefore be mixed with any food in any amount desired.

I have never been able to comprehend how a murderer could be so detached as to let an innocent child, a little girl, partake in that meal. Haack couldn’t feel any hate towards me or my family. We were friends after all, even if under false pretenses and deception. It surely wouldn’t have been that hard for him to somehow distract the child from eating, or to do something else with her. But apparently he was simply indifferent when it came to who had to die along with me. Just as indifferent as his boss Fiedler had been. In the final meeting before Haack’s departure to Israel, he responded to Haack’s question of what to do with the wife and the child, by saying: “That doesn’t matter; we’ll just have to take the risk and accept the inevitable.”

With that he had pronounced their death sentence.

PART III The German Patient (p. 175)

“We have to go back to the King David,” Peter announced suddenly, sitting next to me once again. “I just remembered that I forgot my camera in the room. Maybe they found it and kept it for me. It is worth a try anyway.”

This time I parked the RV right in front of the entrance to the hotel. The concierges looked disconcerted as Peter jumped out of the camper and ran into the hotel. The camera he claimed he had forgotten was all the while in his pants pocket. He was now IMF “Alfons”, once again reporting as ordered back to East Berlin by “district telephone” and announcing that his mission was complete. The conversation was made possible courtesy of the excellent hotel switchboard. Ten minutes later he came out holding up his little Minox from a distance.

“You sure got lucky,” I said to him as he returned.

“Yeah, luck was on my side this time,” he said ambiguously. We drove off.

Susan had ducked out as soon as those first signs of poisoning had so impressively showed up in my wife. She had personally witnessed the amounts I had ingested and felt confident. As a matter of fact, I had devoured 10 times the lethal dose of thallium; an amount that would have “brought down even the toughest of bulls” as my toxicologist would later remark.

Operation Scorpion was not free of risks. Fiedler was clear on that. East Berlin too had a certain respect for the Mossad. Fiedler had faith, however, in the logistical resources of Markus Wolf and his Jewish contacts in Israel. It was actually forbidden to place a top secret agent in enemy operational territory and doing so pretty much risked foiling the operation. He also didn’t like having to make use of the logistical services of the HVA. But how would his IMF be able to operate so far off from the “socialist homeland” without the support of the HVA? It had certainly gathered enough experience in long distance assignments in the course of its multifaceted foreign operations. Israel, with all of its political tensions, had been sought out for that very reason, because there, even with the death of a GDR enemy of the state, nobody would have drawn the conclusion that the MfS had pulled the strings.

IMF “Alfons”, according to his instructions, was to accompany me until the first signs of the effects of the deadly poison became obvious. He was an executioner who observed the slow death of his victim with the curiosity of a professional. The MfS knew the length of the incubation time and had briefed its agent on this. It wouldn’t be much longer.

Meanwhile, we were on our way to Jericho. We were now driving through the Arabic part of Israel, the West Bank, or Galilee, as the Israelis named it according to the Old Testament. It was hot, which led us to shorten our sight-seeing program in passing through. Toward evening we finally reached Nazareth. That is where we spent the night.

The next day our trip continued on to Tiberius on Lake Tiberius [Sea of Galilee]. We stayed for two days at a campground directly on the lake. For our daughter, this was a welcome change. She wasted no time plunging into the water.

The lake was impressive in size. It didn’t attract many tourists, though, and so with the peaceful surroundings and green landscape it was a perfect place to recuperate. Quite the polar opposite to Negev or Sinai!

In the evening of July 25, we drove further north to Safed, or Zefat as the Israelis called it. It was then that I first noticed a tingling in my legs and feet. At that point, I just ignored it for the most part. I chalked it up to the uncomfortable driving position. Safed was 500 feet about sea level, up in the mountains. Winding streets snaked around precipices all the way to the city. Just for a change, we rented a hotel room. My legs continued to tingle ceaselessly even after I was able to move around. I mentioned it to Peter and he said his feet too had apparently fallen asleep. By the time we met for dinner the tingling had only gotten worse. It was bothersome but still no cause for worry.

Haack immediately informed East Berlin from the hotel that the first symptoms of poisoning had set in. The symptoms of thallium intoxication had been discussed at length during the briefings in the East Berlin. He was certain that my complaints were right on schedule for the projected incubation period.

His case officer commanded him to finish his assignment, which included instructions to keep me in Israel to prevent any kind of medical diagnosis or any attempts to save my life. Without further ado he reserved a bungalow under my name in the Moon Valley hotel in Eilat for the next 14 days. That is where he wanted to banish me, far away from any possible qualified medical assistance. Now the time had come for him to abandon me.

Exit Germany ( p. 204)

After this discovery, I no longer doubted that my marriage had failed. And not only that, it looked as though I had also lost my daughter. She didn’t want any more contact with me. But even if you can’t talk about something directly, you don’t have to give the silent treatment. I found an invitation to Berlin on my desk from the Gauck-Agency, short for the Federal Commissioner for Stasi Records. I was granted permission to view my Stasi files. So, I flew to Berlin. In the former headquarters of the MfS, there was a reading room set up. Anyone “wanting to know” could take a place at one of six separate tables. One of the attendants would bring the corresponding files that had been registered and leave them to be read. Apparently, the whole business of studying Stasi files was a painful one. One woman broke out in tears. She sat in front of her files at a loss—the past had caught up with her and shaken her. From other tables there could be heard cries of outrage or loud sneers.

A cart containing files was wheeled up to my table. The attendant stacked a mountain of documents so high that I was completely closed in. I was astonished. So many! I never expected that amount. The files were dated and numbered, starting with the year 1974. They had the handwritten label “Scorpion” on the covers. The more recent the files, the more they contained an ever-growing number of directives, or so-called combative measures, for my extermination. I read and read and couldn’t believe what I was reading. On a notepad I started writing down the real names of the IMs who had been spying on me and the names of all those who had been pulling the strings, those doing the coordinating, order-giving and the order-signing.

I was right in the middle of all of it when there was an announcement that we had to quit for the day. It was already late afternoon and the reading room would be closing. I returned the next day and continued reading. I reviewed the files and sorted and wrote down notes until I got to the file with the register number XV/1890/76-3482/88. The file name was “X” and it was marked with the words “Off-Limits File” as well as “Welsch, Hilde”.

What I then read nearly blew my mind. Page after page contained information on my wife’s cooperation with the MfS, starting back in Sofia. There were protocols, assessments, reports. It couldn’t possibly be true. It was a lie. I clung fast to the belief: all lies. It was all so very cliché. It had to be lies. She couldn’t possibly have done all that. I would have noticed.

With the wind knocked out of me, I read on until I came across long pages of explanations and I immediately recognized her handwriting. It was undeniably hers. It wasn’t faked, forged or imitated. She named names, events, meetings, arrangements, evaluations of our friends and collaborators, described places. In one drawing she gave the layout of her own mother’s apartment with all of its rooms, including the place where she parked her car and the wrought iron garden gate. Even the chair I would sit on when visiting her was marked on the drawing with “Chair, Welsch”.

I suddenly felt ill, like I was going to vomit. I gagged and quickly left the room in search of a toilet.

At the sink I splashed handful upon handful of water on my face. All of my tears had long since dried up. All of my feelings were dead inside. My faith in the world and human beings had been shattered in a single blow. Even before my supposed friend had made his assassination attempts, my wife had already betrayed me to the MfS.

In those moments, I didn’t believe I could go on living. Everything was ruined. Every gesture, every word on every day, was transformed in an instant into the stinking putrid brew of treason. For nearly twenty years, nearly our entire marriage, my wife had lied to me and gone behind my back. She had no conscience.

It took a while for me to calm down.

I returned to the reading room a different person than when I had gone out. I read the assessments, reports and conclusions by the MfS on this operation.

One file folder followed the next. They contained protocols of wiretapped telephone calls, photographs and blueprints of our house, reports by a wide variety of IM’s, reports by intelligence officers, planning and operational reports and a whole bunch of abstruse garbage having to do with theoretical preparations and justifications in preparation of criminal actions with only one purpose, to bring harm to me and to bring me into conflict with society and the governing body in the Federal Republic. I also learned that the MfS had placed one or more IMs in Weinheim.

Who were they? What were there assignments? Had the IM’s spread the rumors that I was dealing weapons or drugs? I came across the answers to my questions only a few pages later. The disgraceful slanders corresponded almost word for word with the secret “Tactical Measures”.

Shortly before the assassination attempt in Israel, the reports stopped. Plans for the attack were presumably contained in another even more clandestine file, which, after the fall of the GDR, was either lost or destroyed in the nick of time, the latter of which was more likely the case.

If you are interested in publishing this book in the USA or in other English-speaking countries, please feel free to contact the author.

[1] Walter Ulbricht was a key politician in the socialist state of GDR, was general secretary of the ruling SED party, Socialist Unity Party and also served as deputy chairman to the Council of Ministers.